Pentateuch, Haphtaroth, and Megiloth.

AUCTION 53 |

Thursday, December 08th,

2011 at 1:00

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts Autograph Letters & Graphic Art

Lot 301

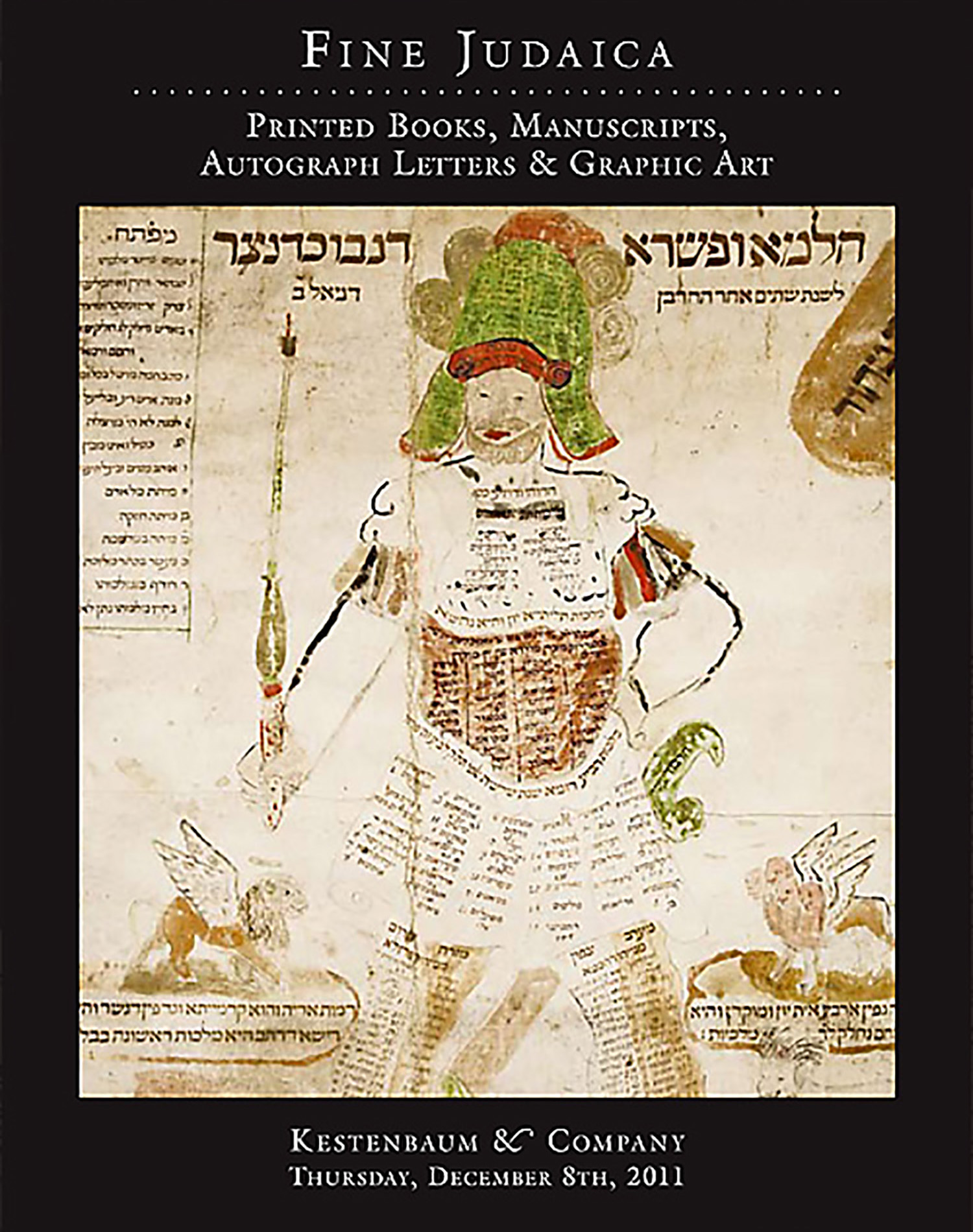

(MEDIEVAL HEBREW ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT LEAVES).

Pentateuch, Haphtaroth, and Megiloth.

Lisbon: Late 15th-century

Est: $12,000 - $18,000

PRICE REALIZED $7,500

The output of what the art historian Gabrielle Sed-Rajna identified as the workshop of copyists and illuminators of Hebrew manuscripts that flourished in Lisbon between 1469 and 1496 represents a high point in the history of Jewish book production. Four of the greatest treasures of the world's finest collection of illuminated Hebrew manuscripts come from this source: the Lisbon Mishneh Torah of 1472, the Lisbon Bible of 1482, the Almanzi Pentateuch and the Duke of Sussex Portuguese Pentateuch, both dated to the decade 1480-90. As many as 30 extant codices may have been produced at, or under the direction of this remarkable operation. Offered here is what remains of a thirty-first production of the Lisbon atelier, retrieved from a binding.

The hunt for lost medieval Hebrew manuscripts that may have survived thanks to being cut up by early modern bookbinders and used as covers, or as paste-downs inside covers, has become a major focus of interest in recent years. Material of this kind is often referred to collectively as the "European Genizah," to suggest a dispersed treasure trove whose scale may prove comparable to that of the Cairo Genizah. Here, however, the term "European Genizah" is, perhaps, not strictly applicable. Marginalia on a few of the fragments in Oriental Hebrew script characteristic of the 16th -18th centuries show that the manuscript had made its way out of Europe, to North Africa or the Middle East, before ending up as "binder's waste."

The surviving fragments, despite some roughness to theur condition, retain much visual as well as scholarly interest - and certainly great presence. The original manuscript itself is, or was, a pocket-sized Pentateuch in which the text is consistently presented as an 18-line single column of just under 3 x 4 inches. Of the 69 folios surviving in various degrees of completeness, the following seven folios feature historiated initial words, illuminated in gold leaf, with highly distinctive penwork in violet ink:

Parashath Terumah (Exodus 25:1 ff.)

Parashath Shelah (Numbers 13:1 ff.)

Haphtarah for Parashath Tazria (II Kings 4:42 ff.)

Haphtarah for Parashath Bo (Jeremiah 13:1 ff.)

"Le-mahar hodesh" phtarah for a Sabbath on the eve of the new moon (I Samuel 20:18 ff.)

Haphtarah for the Second Day of Sukkoth (I Kings 8:2 ff.)

Haphtarah for Shemini Atsereth (I Kings 8:54 ff.)

Five more folios feature decoration in purple ink only:

Parashath Amalek (Exodus 17:11 ff.)

Parashath Yithro (Exodus 18:1 ff.)

Parashath Tazria (Leviticus 12:1 ff.)

Haphtarah for Parashath Mikets (I Kings 3:17 ff.)

Haphtarah for Parashath Vayigash (Ezekiel 37:15 ff.)

It will be apparent from the above that the Haphtaroth, grouped together at the end of the book, are heavily represented. Also present are leaves of the the Pentateuch and a fragment of Koheleth's "To everything there is a season."

Professor Gabrielle Sed-Rajna's conclusion from her minute study of the Lisbon Bible is that it is certain that the decoration was "the work of a team, and several hands can be distinguished." The artists remain anonymous, unlike the scribe who has been identified as Samuel ben Samuel ibn Musa. Sed-Rajna goes on to state that not only is the Lisbon Bible "certainly the masterpiece of the atelier," but, with its accomplished technique and exquisite taste, it sets a new aesthetic standard, followed by several other codices "whose decoration was entirely dependent on the ornamental programme of the Bible." What compels attribution of this fragmentary Pentateuch to the Lisbon atelier is these initial word panels, together with the signature scroll work, executed in violet ink, in what Sed-Rajna calls a "peculiar, highly refined style," which emanates from the panels and which she considers to be probably by the same artist. The panels and scroll work in this fragmentary Pentateuch are not similar to those of the Lisbon Bible but identical. Accordingly, it may be justifiable to go beyond attribution to the workshop of the Lisbon Bible and attribute the decoration of these fragments to the master decorator of the Lisbon Bible itself. Whether the scribe here is ibn Musa cannot be determined by comparison to the script of the Lisbon Bible, since the text in that large-format three-volume work is written in square characters, while this small-format Pentateuch is rendered superbly in a Sephardic rabbinic hand, similar to but distinct from that used in the Duke of Sussex's Portuguese Pentateuch.

For more on the Lisbon workshop, see G. Sed-Rajna's monograph Manuscrits hébreux de Lisbonne: un Atelier de Copistes et d'Enlumineurs au XVe Siècle (1970) and her introduction to the facsimile edition of the British Library's star Hebrew manuscript, The Lisbon Bible 1482 (1988). For the British Library's holdings, see also I. Tahan, Hebrew Manuscripts: The Power of Script and Image (2007). For the European Genizah, see www.hebrewmanuscript.com.