Zacharie, Issachar. Surgical and Practical Observations on the Diseases of the Human Foot.

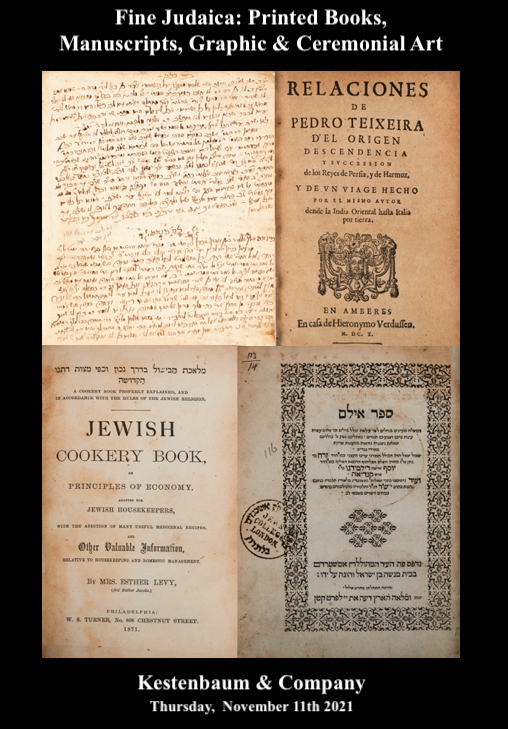

Auction 95 |

Thursday, November 11th,

2021 at 11:00am

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts, Rabbinic Letters, Ceremonial & Graphic Art

Lot 314

(AMERICAN JUDAICA)

Zacharie, Issachar. Surgical and Practical Observations on the Diseases of the Human Foot.

London: 1876

Est: $1,000 - $1,500

An English-born Jewish podiatrist, Issachar Zacharie became President Abraham Lincoln's political confidante and special emissary. Among other things, Zacharie involved himself in helping Lincoln secure the Jewish vote, such as it was, in America. Zacharie’s enigmatic role as friend, emissary, and spy for President Lincoln is a mostly forgotten tributary of American history.

In early 1863, upon discussing the idea of restoring European Jewry to its ancient homeland in Palestine, Lincoln agreed that the vision of a Jewish state in the Holy Land merited consideration: “I myself have regard for the Jews,” he is reported to have said. “My chiropodist is a Jew, and he has so many times ‘put me on my feet’ that I would have no objection to giving his countrymen ‘a leg up.’’ (See Jonathan D. Sarna & Benjamin Shapell, Lincoln and the Jews: A History (2015) p. 140).

Lincoln was referring to Isachar Zacharie, his foot doctor and confidant. Zacharie’s relationship with Lincoln was complex, and aspects of his service to Lincoln and the United States are unclear. Nonetheless, Zacharie most certainly had Lincoln’s confidence and in the president’s mind Zacharie represented American Jewry.

While he never attended college or medical school, Zacharie was trained in chiropody and called himself a doctor. He emigrated to America from England and eventually settled in Washington, DC in 1862. Zacharie’s reputation of successfully treating foot pain attracted the attention of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and soon thereafter, President Lincoln himself. Zacharie and Lincoln exchanged views while Zacharie worked on the president’s feet, and they soon became close friends. Lincoln sought Zacharie’s advice and opinions on matters of state, especially Jewish affairs.

By the end of 1862, Lincoln trusted Zacharie enough to ask him to travel to New Orleans, which had been captured by Union troops. His mission was to mingle with the Southern population and gain a view of its sentiments toward General Nathaniel P. Banks, who had just assumed command of the Department of the Gulf, and Union policies in general. Zacharie recruited a cadre of peddlers to send back vital information, such as Confederate troop movements. Zacharie did his own investigating as well, both to gauge Southern feeling and to watch out for contraband shipments. He did what he could to help New Orleans’ Jews withstand the shortages of food and medication during wartime. He also advised Lincoln to rescind General Ulysses S. Grant’s expulsion of Jews from the Department of the Tennessee.

Recognizing his gift for diplomacy, General Banks enlisted Zacharie in mid-1863 to help him open lines of communication with Confederate leaders. After establishing contacts in Richmond, the Confederate capital, Zacharie returned to Washington and reported to Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward on the opportunity to initiate peace talks. Seward was enthusiastic but other cabinet members strongly opposed the idea. Lincoln decided to grab the initiative and in the Fall of 1863 personally issued Zacharie a pass to the Confederacy.

In Richmond, Zacharie met with Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin (like Zacharie, a Jew) and other Confederate cabinet officers. Zacharie reported that he had secured an agreement on the part of the Confederate leaders to have General Banks represent the Union in peace talks, but again the rest of the Union cabinet rejected the idea of negotiations. According to the New York Herald, Zacharie proposed that the federal government pardon the Confederates and transport them to Mexico, where they would expel the French-supported government of Emperor Maximillian and proclaim Jefferson Davis president. The Southern states would then return to the Union.

Whether this account is true cannot be established, and whether such an idea would be acceptable to Unionists and Confederates alike is speculative. In any event, nothing came of Zacharie’s peace initiative. Eventually, Zacharie gave up hope of being a peacemaker and returned to work as a chiropodist, opening a new office with a partner in Philadelphia.

Continuing to use his influence with Lincoln to help his co-religionists, Zacharie convinced the president to pardon and release Goodman L. Mordecai, a South Carolina Confederate, from a Union prison. A few months later, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln.

Zacharie subsequently continued to back General Banks’ political career and, in 1872, with Banks’ support, applied to Congress for a payment of $45,000 for having treated the feet of 15,000 Union soldiers. The anti-Republican press skewered Zacharie as the President’s conniving “toenail trimmer” who had wanted to enrich himself by creating “a corps of corn doctors, or foot soldiers to put the army in marching order.” Zacharie insisted that he only be paid for the value of the services he performed, but a congressional claims committee rejected his petition.

Zacharie returned to England sometime in 1874, where he resided until his death in 1897. Whatever his or General Banks’ political opponents may have argued