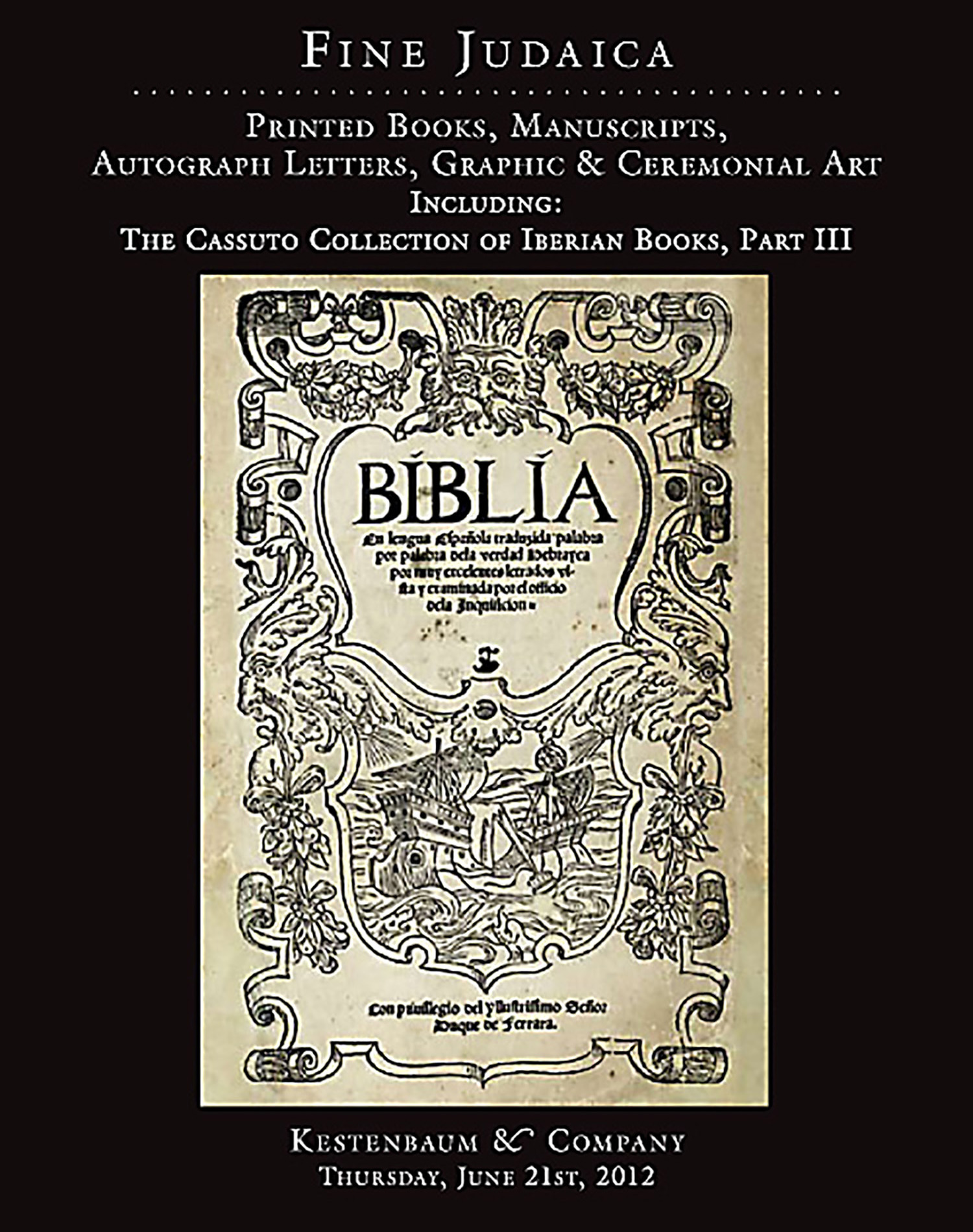

Spanish). Biblia en lengua Española traduzida palabra por palabra dela verdad Hebrayca por muy excelentes letrados vista y examinada por el officio dela Inquisicion.

AUCTION 55 |

Thursday, June 21st,

2012 at 1:00

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts Autograph Letters, Graphic & Ceremonial Art

Lot 307

(BIBLE.

Spanish). Biblia en lengua Española traduzida palabra por palabra dela verdad Hebrayca por muy excelentes letrados vista y examinada por el officio dela Inquisicion.

Ferrara*: 1553

Est: $30,000 - $50,000

PRICE REALIZED $37,000

<<of unparalleled rarity, the Ferrara Bible represents one of the great landmarks in the history of printing.>> It is the first printed Spanish translation of the entire Hebrew Bible, the work of Jews who had carried the language with them into their exile. The Gothic typography and the presswork of this stately folio volume are exceedingly fine. The text, based upon older medieval Castilian versions that had circulated among the Jews of Spain, became virtually canonical for Sephardic Jews in Europe.

<<Historical background:>>

A Jewish community existed in the north Italian city of Ferrara as early as the 13th-century. The local Italian Jews and Aschkenazic Jewish immigrants from Germany, were joined by Jewish exiles from Spain following the expulsion in 1492. Thereafter, Marranos, that is, New Christians, began to arrive in Ferrara with the intention of returning to Judaism. The rulers of the city, the House of Este, valued the contribution to the city’s economy made by these immigrants, and they accorded them privileges, disregarding the fact that they had abandoned Christianity in order to rejoin the Jewish people. This was in stark contrast with most of the towns and cities elsewhere in Italy, in which the Jews were subject to numerous prohibitions and restrictions due to pressure from the Catholic Church.

Conditions of toleration prevailed in Ferrara under the protection of Duke Alphonso and his son Ercole, which allowed for Jewish printing to flourish beginning in the 1550s. Vernacular books intended for Marranos who had lost familiarity with the Hebrew language were produced. Basic texts of Judaism, especially the liturgy and the Bible, were an imperative. Texts in the Spanish language were preferred, both because of a tradition of translation of sacred texts into that language dating back to the Middle Ages, and also because many of the Marranos were descended from exiles from Spain and knew Castilian well.

<<The Text:>>

Completed on March 1st, 1553, the Ferrara Bible is a remarkable achievement. The entire Spanish text is obviously Jewish from beginning to end, avoiding all the Christological nuances and mistranslations of the Vulgate. There is much discussion among scholars regarding variant issue-points, yet it is clear that all versions of the Ferrara Bible, no matter their variant, are fundamentally Jewish and ultimately represent a single edition.

The title page of the Bible proclaims that it is a “ word for word translation from the Hebraic Truth.” It also states that the translation was “seen and examined by the Office of the Inquisition.” On the bottom of the page is recorded that the book was printed “under a privilege from the Duke of Ferrara.” There is no doubt that the Duke permitted the Jews to print the book, but it is inconceivable that this translation could have been approved by the Inquisition. The Catholic Church would have approved of no translation other than the Vulgate, which was its official version. Moreover, it would not have given approval to a translation based upon the Hebrew text, edited in a style that was faithful to the traditional Jewish Bible commentaries. Aside from that, authorizations by the Inquisition never appeared as part of the title of a book, but rather as a seal on the title page or the last page. Such authorizations did not refer to the “Office of the Inquisition,” but rather to the “Holy Office” (Santo oficio). Most likely the formula printed here on the title page was coined for the sake of appearances and Duke Ercole II probably agreed to this deception.

Important to note is the tragic iconography of the title-page which is truly emblematic of the entire era. In the top center of the ornate woodcut frame is the head of a bearded Neptune, who, with bulging cheeks, is blowing a storm. Beneath the lines of text, a ship flounders in the waves of a raging sea, its sails torn, its mast broken. The ship represents the afflicted Jewish people, particularly the Spanish and Portuguese exiles, in their perilous search for a safe haven. Further symbolism may be found: At the top of one of the masts there is an armillary sphere which represents a dramatically inverted symmetry. The very same device that was for Portugal, a sign of its great age of exploration and its hope for glory, becomes here, a symbol of Jewry’s latest age of wandering, and its hope for a secure refuge from the storm of its sufferings.

<<The Ferrara Bible, a masterpiece of 16th-century Jewish book production, became the classic Spanish version of the Bible for the Marranos who returned to Judaism and indeed for the entire Sephardic Diaspora as a whole, for centuries thereafter.>>

For a penetrating historical insight to the Ferrara Bible, see Y.H. Yerushalmi & J.V. de Pina Martins’ edition of S. Usques’, Consolacao as Tribilacoes de Israel (1989) pp. 84-93.

See also C. Roth, The Marrano Press at Ferrara 1552-1555 in: Modern Language Review, XXXVIII (1948) pp. 307-317. See also the careful and judicious analysis of almost all extant copies by S. Rypins, The Ferrara Bible at Press (London, 1955).