Nebuchadnezzar's Dream and its Interpretation, in the Second Year after the Destruction.

AUCTION 53 |

Thursday, December 08th,

2011 at 1:00

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts Autograph Letters & Graphic Art

Lot 322

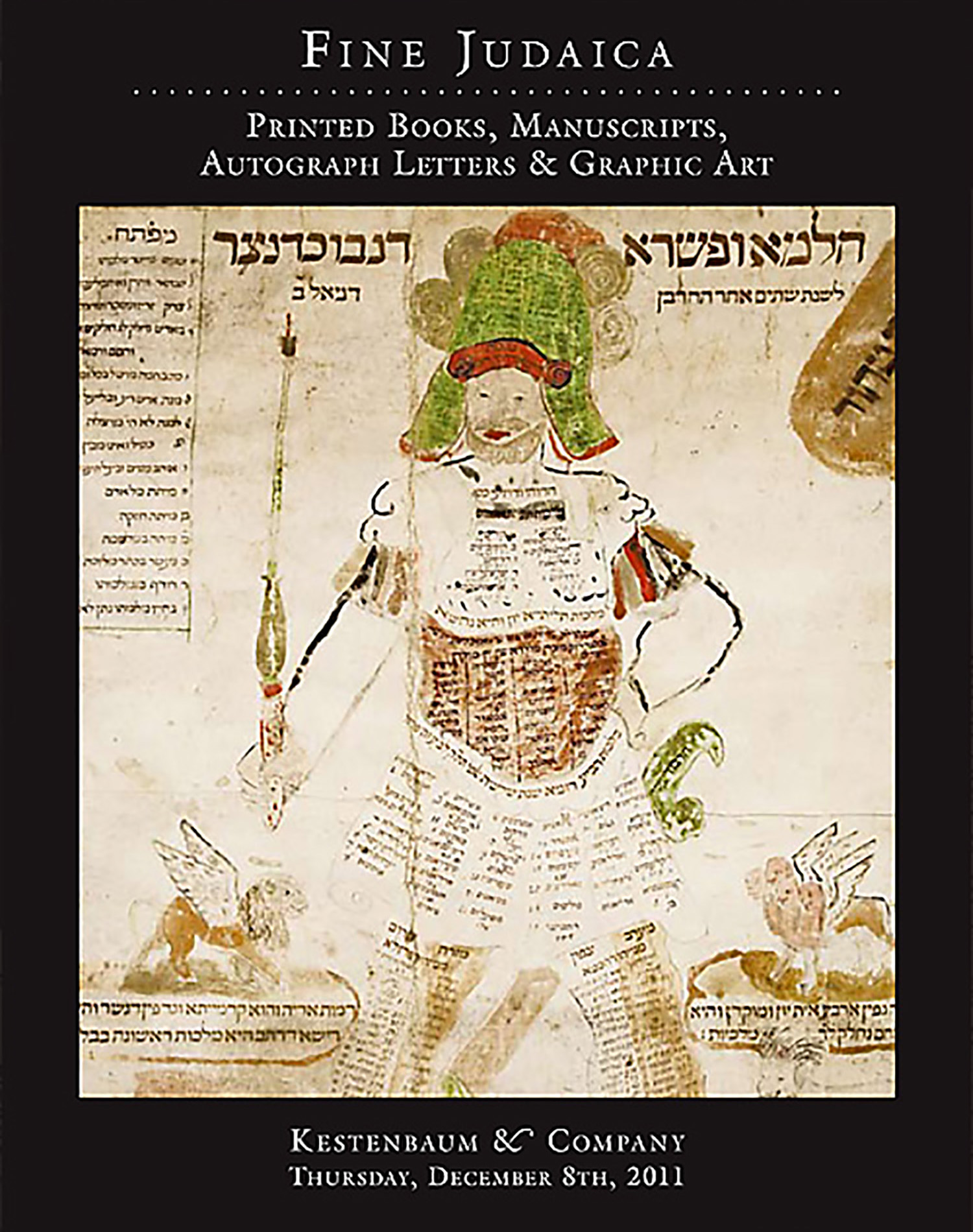

A MOST UNUSUAL ILLUMINATED VELLUM LEAF.

Nebuchadnezzar's Dream and its Interpretation, in the Second Year after the Destruction.

Est: $10,000 - $15,000

PRICE REALIZED $24,000

Nebuchadnezzar's Dream and its Interpretation, in the Second Year.

after the Destruction.

Extraordinary graphic testimony to the millenarian and antiquarian.

interests of an Ashkenazic Jewish intellectual of the late Early.

Modern/early Enlightenment period.

Ink and watercolor on vellum.

24 x 20 inches.

[Central Europe, 1711-14]

The full height of this monumental undertaking, apparently unique in.

the annals of Jewish art, is given over to the depiction of King.

Nebuchadnezzar's vision, related in Aramaic in the second chapter of.

the Book of Daniel. Selected for his intelligence and looks, young.

Daniel, from one of the leading families of Judah, is taken back to.

Babylon after Nebuchadnezzar's conquest, to train as a courtier. Soon,.

Nebuchadnezzar sees in a dream the statue of man, with head of gold,.

chest of silver, belly of bronze, and legs of iron, which end in feet.

of iron and clay. A great rock falls on the statue, smashes it, and.

proceeds to cover the whole earth. The wise men are at a loss, but.

Daniel prays for illumination, then offers an interpretation that.

satisfies the king: each of the metal tiers corresponds to one of the.

empires destined successively to dominate the world. Crushing the last.

of these empires will usher in the Kingdom of Heaven. Gold represents.

Babylon, and pre-modern readers, Jews and Christians, have almost.

always understood silver to be Persia, bronze Greece, and iron Rome.

This is the view of Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer, Rashi, and ibn Ezra among.

medieval Jewish commentators, and here, too, the statue is rendered.

thus. The beard is golden (if not the helmet); the belly of bronze is.

dark brown; chest and thighs are left uncolored to suggest silver and.

iron; and the calves and feet of iron and earth are represented by.

stripes of uncolored iron and light brown clay.

What might otherwise be charming folk-art becomes much more than.

that, a historical document of uncommon interest, thanks to the mass.

of data inserted, in the square and semi-cursive Hebrew script of a.

true adept, within the statue's outline. Here is to be found a.

comprehensive numbered list of each of the monarchs of all four world.

empires. The helmet is covered in the names of the Assyrian and.

Chaldean rulers of ancient Babylon, in flawless, near-microscopic,.

rabbinic Hebrew characters. Now in square characters, the chest area.

accommodates easily the ten rulers of the short-lived Persian Empire.

The mid-section is divided into four columns, listing the rulers of.

each of Alexander's Hellenistic successor states. Then, on the kilt,.

comes Rome, with Julius Caesar at no. 1, followed by Augustus,.

Tiberius, Caligula and all the rest down to the division of the Empire.

in 285. Here, in a tour de force of miniaturization, the statue's.

powerful legs are composed once more of tiny rabbinic script,.

inevitably so in view of the enormous number of names to be contained.

On the right leg are all the Byzantine emperors, followed by their.

Ottoman successors, while the left leg displays a list of Holy Roman.

emperors. On either side of the statue, rendered with great verve, are.

the four beasts encountered in Daniel's own dream (Daniel 7), which.

complement in their symbolic significance the four-part division in.

Nebuchadnezzar's vision. The winged lion is Babylon, the bear (looking.

more like a boar) is Persia; the panther with four heads is the.

four-part Greek empire; and the fiercest creature, with ten horns and.

resembling no known species, is Rome. The ten horns correspond to the.

ten toes of the statue's feet of clay. Here, the toes on the Ottoman.

foot are marked Africa, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and (big toe)

Asia; the toes on the other foot are France, England, Italy, Spain,.

and (big toe) Ashkenaz, the German-speaking lands. A key identifies 15.

alphabetical or astrological symbols, intended for use in.

characterizing the reigns of some of these monarchs. The presence of a.

Sun sign (shemesh) indicates a just and able ruler; Saturn denotes a.

magnanimous and philanthropic one; Jupiter: energetic and successful;

Mars: peace-loving, wise, and crafty; the Sun again (as kochav hamah):

omnipotent; Venus: evil or worthless; increscent Moon: unsuccessful;

and decrescent Moon: a fool or imbecile. Other symbols indicate:

promiscuity and hedonism; date of death and whether natural, painful,.

or in combat; date of coronation; and date or fact of deposition or.

abdication.

The document is anonymous and undated, but possible years of.

production can be limited simply by using the historical data.

presented. At compilation, the reigning Ottoman sultan was Ahmed III.

(ruled 1703-30), the reigning Holy Roman emperor Charles VI (ruled.

1711-40). That places the document within the years 1711-30. The.

garter worn by the statue on its left leg may offer more precision. It.

bears the legend "Das Spanishe Hoyz," the only Yiddish in the.

document. The garter marks the point, in 1438, after which all Holy.

Roman emperors were members or descendants of the House of Habsburg.

From 1506 until 1700, the Habsburgs reigned over the vast Spanish.

Empire as well. Want of a direct male heir resulted in the War of the.

Spanish Succession, which dragged on until the Habsburgs surrendered.

to the Bourbons, in 1714, of their claim to Spain. Charles VI,.

therefore, was Holy Roman Emperor and would-be head of the House of.

Spain for the three years 1711-14 only.

The Reformation, with its emphasis on biblical interpretation and.

its antipathy to Rome, transformed the importance of Daniel 2 and 7.

Soon, especially in radical circles, these chapters were exciting as.

much passion as any in the Bible. Daniel became a framework for the.

systematic understanding of world history. Similarly, it was widely.

supposed to hold the key to future history, becoming the point of.

departure for a whole literature of apocalyptic speculation, which.

continues to flourish as much as it ever did, so that the toes of the.

statue and the horns of the beast are identified in some circles with.

the European Union. This obsession with eschatology, especially the.

downfall of the fourth empire and the messianic new order that would.

take its place, possibly featuring the restoration of the Jews to.

their ancestral land as centerpiece, reached its peak in the mid-17th.

century, with widespread expectations for 1648. The Chmelnitski.

massacres certainly made the year apocalyptic enough for the Jews in.

eastern Europe, sending many refugees west, especially to Amsterdam.

Charles' I's execution in London in 1649 kept things on the boil, and.

in the Netherlands, especially, an intellectual elite was consumed.

with these ideas, and hungry for information from reliable Jewish.

sources, much of it provided by Menasseh ben Israel, whose Hope of.

Israel contributed significantly to apocalyptic expectation. The.

Sabbatean debacle of the 1660s, too, fed and was fed by this.

pan-European sense of expectation. Alongside all of this, Daniel.

became an increasingly popular theme in art, most notably as.

represented by Rembrandt in several paintings and in the engravings he.

prepared for Menasseh's Spanish-language exposition of Daniel 2, La.

Piedra Gloriosa: the glorious rock that shatters Nebuchadnezzar's.

statue. Schematic representations, albeit simple ones, of the visions.

in the Book of Daniel appeared in print, one in Germany as early as.

1529. This Hebrew version, spectacular in its thoroughness and.

execution, also intrigues as fresh evidence of the absorption into a.

Jewish milieu of the new ideas prevalent about the book of Daniel,.

privileging it as it does as the matrix in which to construct a.

timeline of world history. Still, the interest here seems more.

"academic" than pragmatic. For want of any obvious inclination to.

calculate the time of the redemption, it seems as if the artist was.

motivated to carry out this elaborate project more by intellectual.

curiosity and for fun.

For more on Jewish-Christian intellectual exchange on the subject of.

the millennium in baroque Europe, see D. Katz, J. Israel, and R.H.

Popkin (eds.), Sceptics, Millenarians, and Jews (1990). For the.

millennium as a theme in western art, see A. Bokern and P. Gördüren,.

Die letzten Dinge: Jahrhundertwende und Jahrhundertende in der.

bildenden Kunst um 1500 und 2000 (1999)