Kalmanovitch, Zelig. A collection of surveys and translations into German of the history and literature of the Karaites. Typed carbon copy with numerous and detailed autograph corrections

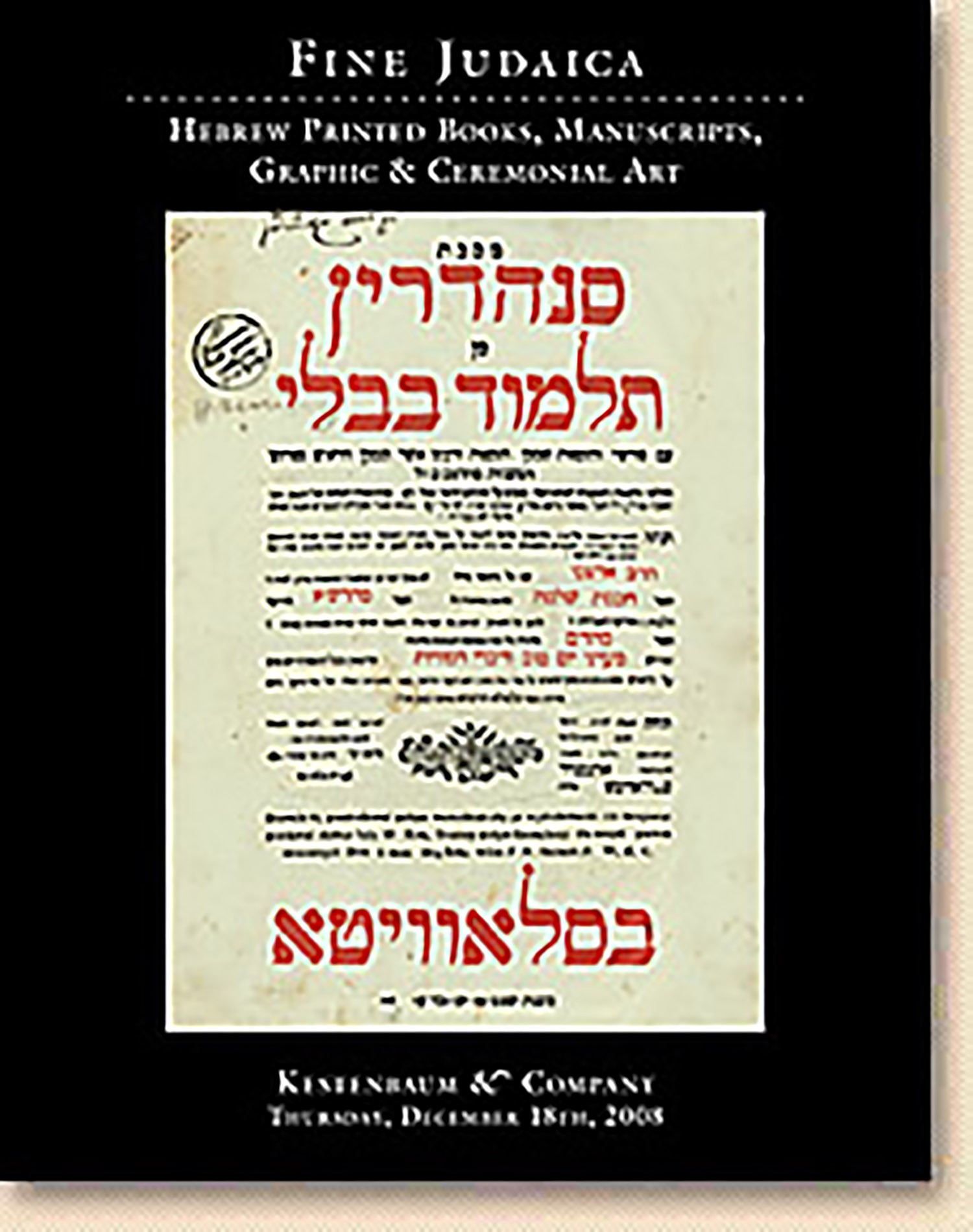

AUCTION 42 |

Thursday, December 18th,

2008 at 1:00

Fine Judaica: Hebrew Printed Books, Manuscripts, Graphic & Ceremonial Art

Lot 304

(KARAITICA).

Kalmanovitch, Zelig. A collection of surveys and translations into German of the history and literature of the Karaites. Typed carbon copy with numerous and detailed autograph corrections

Vilna: October, 1942

Est: $1,200 - $1,800

In June 1941, the Nazis queried the “Racial Psychology” of the Karaites in order to determine whether they belonged to the Jewish people. The scholarship of Zelig Kalmanovitch, then director of Yivo, was brought to bear on this issue. In order to save the Karaites from certain destruction, Kalmanovich opined that they were not of Jewish origin. As a result, the Karaites escaped the Nazi era unscathed.

In Kalmanovitch’s Hebrew diary, miraculously discovered in Vilna after the War, he writes how the Nazis demanded he “make a survey of the literature about the Karaites” and “write a history of the Karaites and of their present condition” (August 9, 1942). Later, Kalmanovitch was taken to the home of the Karaite Hakham of Vilna, Seraiah Shapsal, where he was shown the Karaite archives (May 26, 1943). It is not clear whether the purpose of the visit was to view the archival material or rather to have the Karaite scholar correct the proofs of Kalmanovitch’s translation of Shapsal’s Russian tome on the Karaites. (Seraiah Khan Shapsal, a former senior Russian official, was recognized in 1932 by the Polish Ministry of Culture and Education as Hakham of Troki, a traditional Karaite stonghold outside Vilna, and spiritual leader of the Polish Karaites.)

Ostensibly, the origins of the Karaites, or “Bnei Mikra” (“People of the Scripture”) as they refer to themselves, lie in an eighth-century schism between Anan ben David and his younger brother over the succession to the throne of the Babylonian exilarchate. Anan and his followers rejected the authority of the Oral Law or Talmud and developed a Judaism based solely on Scripture. With time, the gap between the Karaites and the Rabbanites widened so, that in modern times various attempts were made by Karaites to portray themelves to the outside world as a nation apart from the Jews. Prof. Philip E. Miller has documented one such attempt in the early nineteenth century, when Simcha Babovich, leader of the Crimean Karaites, successfully inveighed the Tsarist government in St. Petersburg to create a separate Karaite Religious Consistory, whereby Karaite youths were exempted from the compulsory conscription into the Russian military that harrowed the Jewish community.

Zelig Hirsch Kalmanovitch (1881-1943) received a traditional rabbinic education in Goldingen, Kurland. He went on to study Semitic philology and history at the Universities of Berlin and Königsberg. In 1929, he settled in Vilna, becoming the editor of the Yivo Bleter. The only member of Yivo Institute to remain in Vilna under the Nazi occupation, Kalmanovitch single-handedly carried on the historical and archival work of Yivo, until September 1943, when he and his wife Rivele were deported to an extermination camp in Estonia.

See Z. Kalmanovitch, “A Diary of the Nazi Ghetto in Vilna,” YIVO Annual of Jewish Social Science, Vol. VIII (1954), pp. 23,29,50,52,54; M. Dworzecki, Yerushalayim de-Lita in Kamf un Umkum (1948), p.243; P.E. Miller, Karaite Separatism in Nineteenth-Century Russia (1993); EJ, Vol. II, cols. 919-922; Vol. X, cols. 761-85