Me’or Einaim [Philosophy of History]

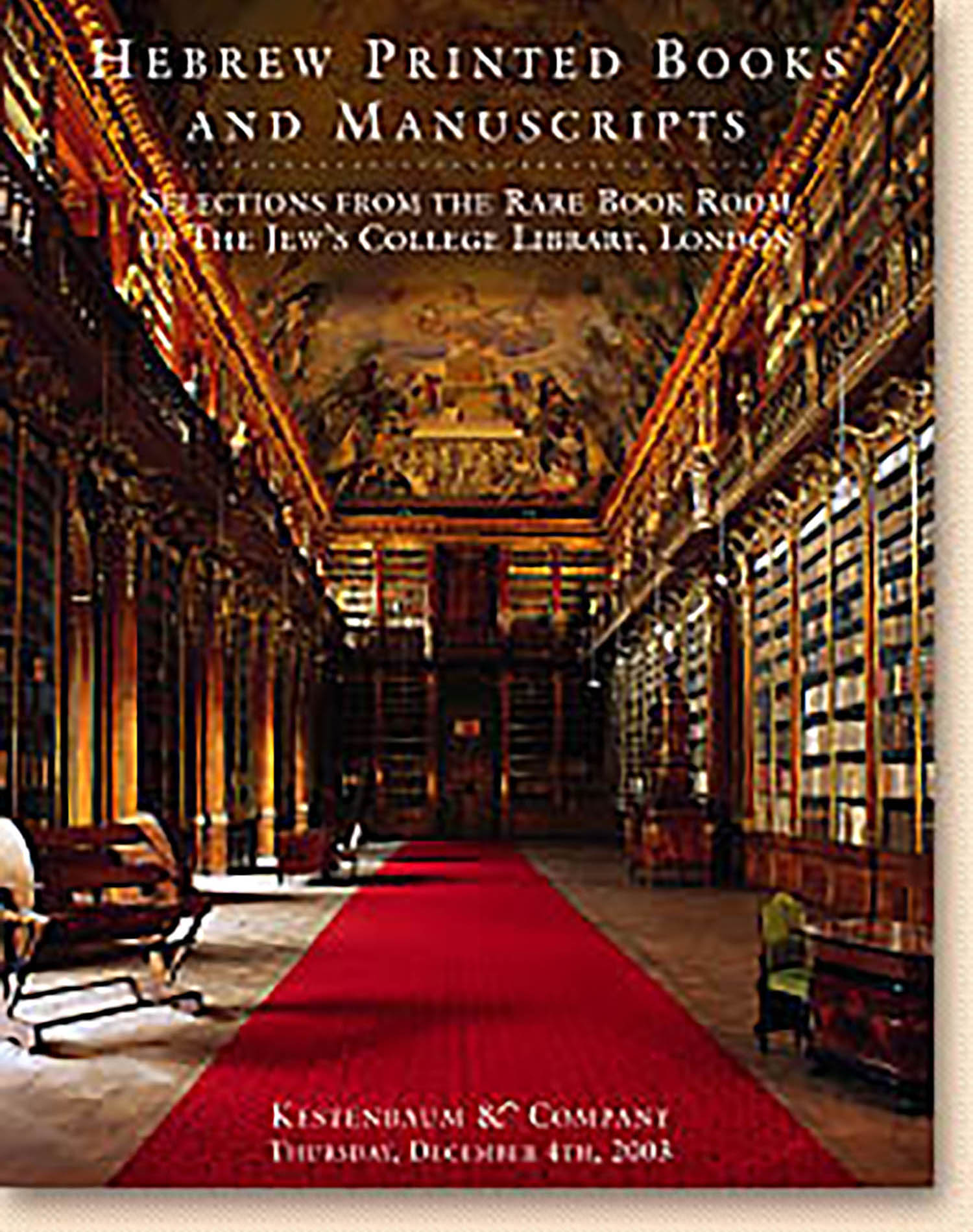

AUCTION 21 |

Thursday, December 04th,

2003 at 1:00

Kestenbaum & Company Holds Inaugural Auction of Hebrew Printed Books & Manuscripts at Their New Galleries

Lot 69

DE ROSSI, AZARIAH

Me’or Einaim [Philosophy of History]

Mantua: n.p 1574

Est: $1,500 - $2,000

PRICE REALIZED $2,750

“... The Me’or Einaim became so important that it rendered its author as one of the greatest, or perhaps the very greatest, of Jewish historians who flourished in the seventeen centuries between Josephus and Jost.” S. Baron, Azariah de Rossi’s Attitude to Life, in: Studies in Memory of I. Abrahams, (1927) p.12.

Azariah de Rossi, was a member of an Italian Jewish family that traced its ancestry back to the time of Titus and the destruction of Jerusalem. His controversial Me’or Einaim questioned conventional medieval wisdom and introduced fundamental changes in chronology.

De Rossi rehabilitated the works of the Jewish philosopher Philo, who had been ignored by Jewish scholars for almost 1500 years. He exposed the Jossipon as an early Medieval compilation based on the works of Josephus, though with much falsification. In the spirit of the Renaissance, de Rossi turned to critical analysis and made use of the Apocrypha and Jewish-Hellenistic sources in his study of ancient Jewish history and texts. Most contentiously, he suggested that Midrashic literature was employed as a stylistic device “to induce a good state of mind among readers,” and thus should not be understood to be literal. Such statements led the Me’or Einaim to be viewed as heresy and it was banned by the rabbinic authorities upon publication. He reissued the work the same year, making changes to the offending passages and adding an apologetic postscript. However, some prominent rabbis decreed youth below the age of 25 be prevented from consulting the book. De Rossi himself was spared chastisement due to his personal observance of halachic practice. See Carmilly-Weinberger, pp.210-13; I. Mehlman, Gnuzoth Sepharim, (1976) pp.21-39