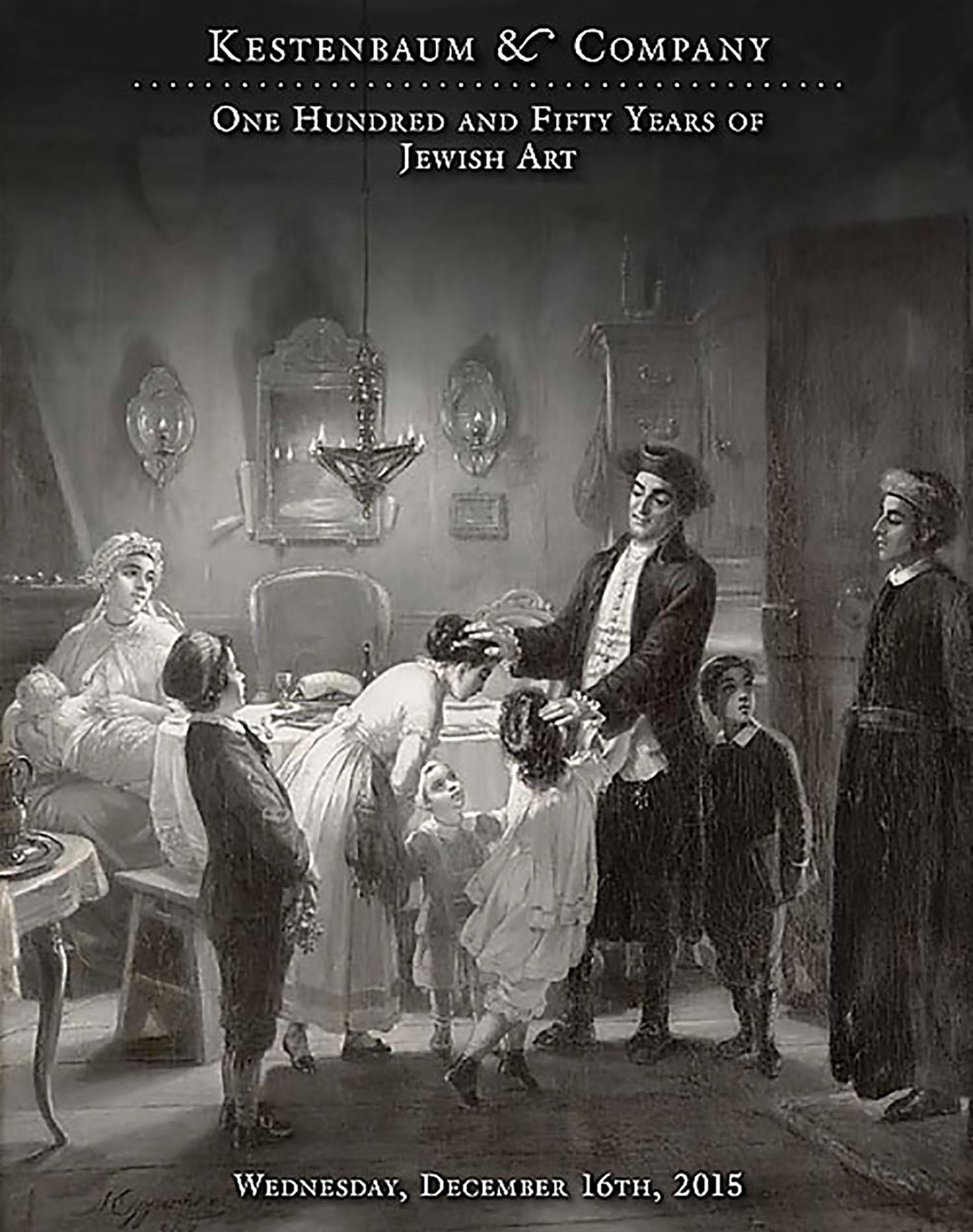

Freitag Abend.

AUCTION 67 |

Wednesday, December 16th,

2015 at 1:00

One Hundred and Fifty Years of Jewish Art

Lot 4

OPPENHEIM, MORITZ DANIEL.

Freitag Abend.

German, (1799-1882):

Est: $300,000 - $500,000

PRICE REALIZED $380,000

This beautiful painting is one of the most beloved of Oppenheim’s series entitled Bilder aus dem Altjüdischen Familien-Leben (“Pictures of Traditional Jewish Family Life”), hailed as a watershed in it’s perception of Jews in the 19th century. For almost the first time in European history, Jewish life was presented as an intimate ceremonial, in which the participants were represented as well-dressed, dignified and pious model members of well-to-do bourgeois society.

In the 1850’s, German-Jewish artist Moritz Oppenheim commenced work on a series of Jewish genre scenes in color, representing hallmarks from the religious calendar year that feature ceremonies and traditions of Jewish life, in the home, the synagogue and the community. Soon after, Frankfurt publisher Heinrich Keller commissioned Oppenheim to recreate these paintings in tones of grey, or grisaille, to facilitate efficient photomechanical reproduction, for the technology of the time was inadequate to reproduce color paintings. Ultimately, Oppenheim’s Jewish life-cycle were depicted in twenty scenes, published in full in a deluxe edition in 1882.

In addition to reasons of functionality as most efficient for reproduction, the grisaille method is also selected by artists in order to create a visual effect resembling sculptural relief. This aesthetic preference allowed for a normally dynamic painted scene to be altered to an appearance of timelessness.

Oppenheim’s grisaille paintings remained in the possession of the publisher Keller until the beginning of the 20th century. Most were subsequently acquired by the Cramer family of Frankfurt, who emigrated to London in the 1930’s, taking the paintings with them. In the early 1950’s the pictures were sold, later coming into possession of the Jewish Museum New York, a gift of the late Oscar & Regina Gruss. Many of Oppenheim’s paintings and drawings that remained in Germany were lost during World War II.

<<THE ARTIST.>>

Considered as the greatest Jewish artist of his time, Moritz Daniel Oppenheim was born to Orthodox Jewish parents in 1800 in the industrial town of Hanau, not far from Frankfurt. He was eleven years old when the Frankfurt Ghetto was abolished in response to Napoleon’s 1806 Confederation of the Rhine and the 1810 Constitution of the Grand Duchy in Frankfurt. Oppenheim studied at the Munich Academy of Arts and furthered his education in Paris. He then moved to Italy where he lived in Rome, often travelling to Naples where he interacted with Baron Carl Mayer von Rothschild to whom he sold several paintings. Oppenheim’s Grand Tour of Europe continued via Bologna, Venice and Munich, returning to Frankfurt in 1825. He was commissioned to paint portraits of politically notable Germans including Karl Ludwig Börne (1827), Heinrich Heine (1831), the five Rothschild brothers (1836) and Gabriel Riesser (1840).

Oppenheim developed a close friendship with Gabriel Riesser, who had been presented by the Jewish community of Baden with Oppenheim’s painting “The Return of the Jewish Volunteer” (1833) in appreciation of the former’s efforts in seeking civil rights for the Jews of Germany. The painting depicts a Jewish soldier following the Wars of Liberation, returning to his family, who are clearly depicted as observant of a traditional Jewish lifestyle. The painting represented the belief Oppenheim shared with many in the German-Jewish community of the time: One can be both German and Jewish without contradiction. Similarly, albeit perhaps less politically charged than in an image of a volunteer soldier, Freitag Abend portrays Jews observing the customs of their faith, comfortably intertwined with a particular German sense of Gemütlichkeit.

Oppenheim remained true to his faith and unlike many other German Jews active in the arts, did not convert to Christianity, indeed it appears that he was a member of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch’s Israelitische Religions-Gesellschaft.

<<The Historical Context.>>

Like the French Calvinist engraver Bernard Picart (1673-1733) a century earlier, Oppenheim created a new stage for presenting observant Jewish life and custom as an ethnographic study. In his 1723 work “Cérémonies et Coutumes Religieuses de tous les Peuples du Monde,” Picart depicts the religious ceremonies and customs of the Jews of Amsterdam. Interestingly, Picart’s twenty engravings relate to Oppenheim’s twenty grisaille paintings of the Bilder series, including many synagogue scenes. However more than half of Oppenheim’s images are set within the home, ensconced amidst family. This difference is indicative of the life of each respective artist: Where Picart was acting as a recorder of traditional Jewish culture, Oppenheim was living it.

The seemingly anachronistic setting of the old Frankfurt ghetto, cast with characters dressed in 18th century costume, was chosen by Oppenheim for his Bilder series to appeal to the conservative values of the 19th century German-Jewish bourgeoisie. The Jewish Ghetto, pre-Emancipation, was presented as an intimate, almost utopian religious arena, well at ease with itself, and quite comfortable without the presence of the secular authorities and their varied limitations on Jewish life. Oppenheim’s decision to depict the “Altjüdischen” in his series was in response to the proponents of the Haskalah, or Enlightenment movement, who sought to reprogram Jewish society to better acclimate to modern society by abandoning seemingly archaic religious traditions.

There is irony in the presence of religious ceremonies and custom as central to images produced for a clientele of varied religious demographics. Where Oppenheim was a member of the neo-Orthodox community that directly opposed the Reform (who abolished most all Jewish religious observances - including the Sabbath), our painting’s subjects serenely celebrate together, a tableaux of intimate Sabbath warmth.

<<The Scene.>>

The present painting, Freitag Abend (Friday Night Blessings), is perhaps the most emotionally evocative of all of Oppenheim’s Bilder. The scene of religious and domestic harmony conjures up many nostalgic motifs while symbolic of the faith and values both of the family represented and indeed the artist himself.

In a survey of the idealized 18th-century setting and dramatis personae, we begin at center, with the father, just returned from the synagogue and Friday evening prayers. He is greeted by his children, the two daughters leaning forward to receive their paternal blessing. The eldest son at the left appears to be holding a posy of flowers, the younger son at center, dressed in his tzitzith, looking up at his father and the middle son at right distracted by the exotic visitor at the room’s perimeter. The mother in her shterntykhl head-covering sits with baby at a table set for the festive Sabbath meal: Wine and silver goblet ready for the Kiddush ritual, the challah-loaves peeking out from under a silk covering. The customary appetizer for Sabbath dinner, a plattered fish, can be seen and in the background, apples roast on a stove-top, a German winter delicacy.

Other ritual items around the comfortable room include a prominent Judenstern, or Sabbath hanging-lamp, while atop the bureau sits a spice tower and braided candle for the Havdolo ceremony and a charity box. A tallith bag hangs nearby, a framed Mizrach sign is affixed to the back wall and a water ewer and basin for hand-washing appears at far left (a notable detail omitted from the Keller reproduction).

At the far right side of the painting, observing his host family, is a young Polish guest, adorned in his distinct regional style of dress influenced by the Polish gentry or “szlachta.” The character of the Polish visitor can often be seen in other paintings by Oppenheim. Despite social and cultural tension between emancipated German Jews and East European Aschkenazim, in this painting the young man is welcomed as an honored guest. Oppenheim sought to demonstrate the mutual respect between two regional Jewish traditions and the commonality achieved via the rituals of the Sabbath.

This painting, alongside the entire Oppenheim series of Bilder aus dem Altjüdischen Familienleben, heralds traditional Jewish values as timeless and enduring, enabling a community to persist and thrive despite the vicissitudes of contemporay life.

Due to the popular appeal of the Bilder Moritz Oppenheim has achieved status as the foremost Jewish artist of the past two centuries.

<<Provenance:>>

The late Sara and the late Julian House, Phoenix, Arizona.

Thence by family descent to the present owners.

<<Exhibited:>>

The Jewish Museum, New York, 1993-95.

Das Jüdische Museum, Frankfurt, 1999-2000.

<<References:>>

Jewish Museum Frankfurt Catalogue, Moritz Daniel Oppenheim: Jewish Identity in 19th Century Art (1999) p. 289 (illus).

Israel Museum Catalogue, Moritz Oppenheim: The First Jewish Painter (1983).

An academic essay relating to this painting, along with more expansive notes to the present catalogue-entry, are both available upon request.